Game Changers

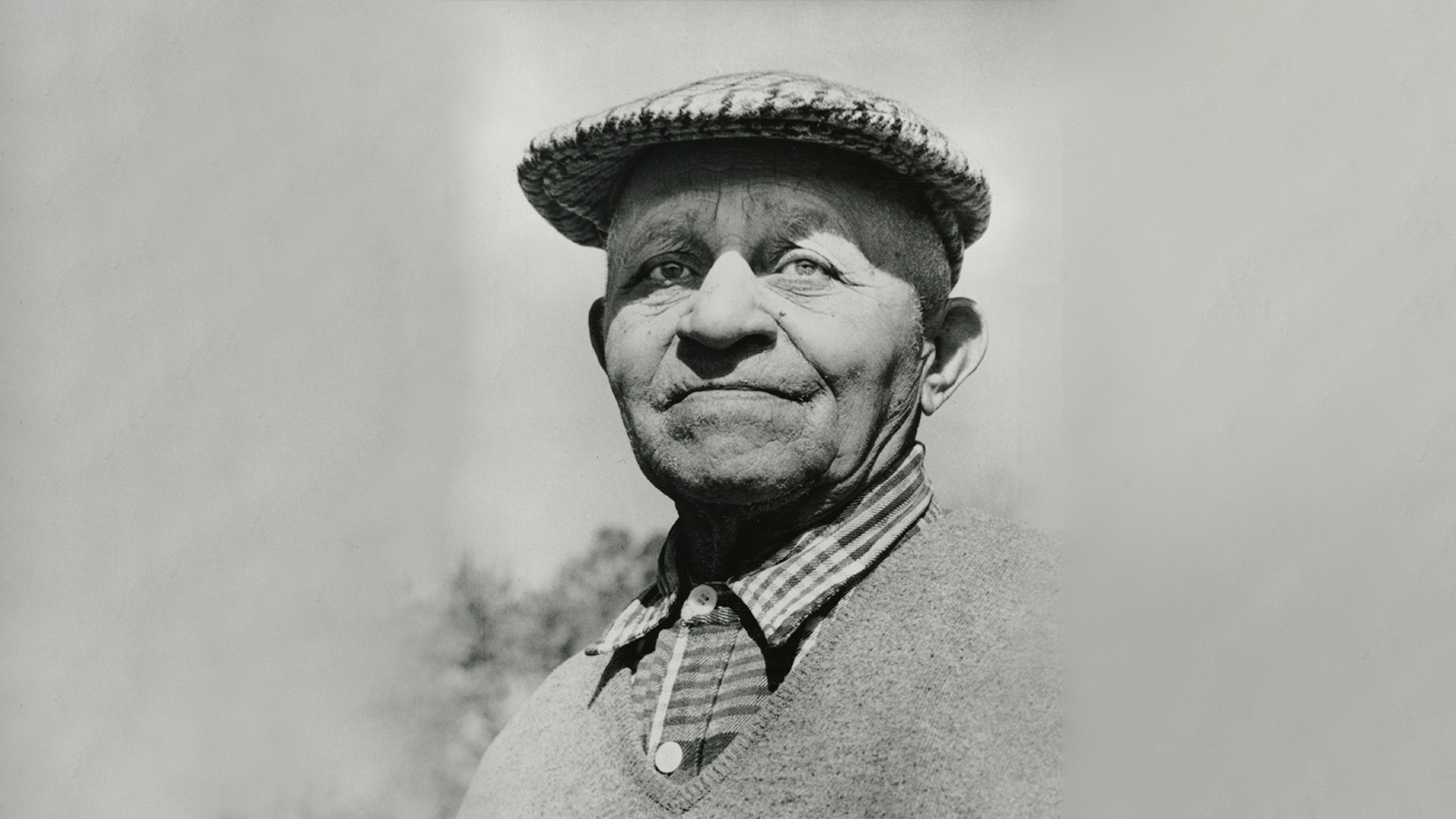

PGA Professional John Shippen and the Preservation of a Pioneering Legacy

By Bob Denney, PGA Historian Emeritus

Published on

Aronimink Golf Club’s hosting the KPMG Women’s PGA Championship this week is the most recent of many milestones in the facility’s 124-year history.

More than a century ago, Aronimink took a bold step to advance diversity in golf without fanfare and with most of its membership unaware of its significance.

In 1899, John Shippen Jr. - then a 19-year-old golf professional and a native of the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C. - was hired as Aronimink’s second head professional. He brought his brother, Cyrus, as his assistant, and the two would represent Aronimink that year in the U.S. Open at Baltimore Country Club.

Three years earlier Shippen had made history as the first Black golf professional in the U.S. when he was hired as the first head professional at Maidstone Club in Easthampton, New York. There’s more to Shippen’s legacy as a pioneer in golf: In 1896 at age 16, he became the first American-born golf professional in the United States. Prior to Shippen, golf professional jobs were primarily held by immigrants from the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Despite his groundbreaking role as a Black golf professional, there were those who curiously refused to acknowledge Shippen’s Black ancestry, which enabled an inaccurate narrative that he was of Native American descent to remain in circulation for generations.

Shippen was the son of a Presbyterian minister, educated at Howard University, who was sent by the church to set up a ministry on the Shinnecock reservation in Southampton, New York. The reservation adjoined famed Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, where young John would become an outstanding golfer. Shippen’s time on the Shinnecock reservation is likely the source of confusion and also an attempt at concocting an acceptable, if inaccurate, justification for those who hired him later in his career.

In 1899, a memo was published by the Greens Committee of Aronimink Golf Club and is on file in the Temple University archives in Philadelphia.

The memo incorrectly noted that Shippen “is a direct descendant of John Raife and Pocahontas, and is not of African descent, as generally reported.” The memo also falsely claimed that Shippen’s parents “on one side were Indians, belonging to the Pocahontas tribe, and on the other side from an Englishman, named Alex Spotswood.”

Diving deeper into Shippen’s heritage, a number of supporters have put misconceptions about this golf professional who rose above prejudice to rest. Among them were archivists, federal census records, the Virginia Historical Society, Howard University, the New York Public Library, the USGA and ancestral historians including his own late daughters, Beulah and Mabel.

Shippen’s daughters charted the family tree from the first generation of Blacks born free following the end of the Civil War, finding that John’s paternal grandfather was an enslaved person on a Virginia plantation. The daughters’ investigation squashed the “legend” that Shippen was either Native American or half-Black and half-Native American.

As late as 2018, a profile written by the New Jersey State Golf Association Hall of Fame listed Shippen as half-Black and half-Native American.

Thurman and Ruby Simmons of Scotch Plains, New Jersey, became Shippen defenders, researching the golfer who competed in four U.S. Opens and who made an impact on their small community.

Founded in 1921, Shady Rest Golf and Country Club (today’s Scotch Hills Country Club) was the country’s first Black-owned and African American golf and country club. The club was the home to prominent entertainers such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Cab Calloway.

Shippen served as the club’s head professional for more than 30 years, retiring in 1960. He died in 1968 in Newark, New Jersey. In 2009, the PGA of America bestowed Shippen with posthumous membership. Thurman Simmons and Shippen’s late grandson, Hanno Smith, attended the ceremony at the PGA Annual Meeting in New Orleans.

Thurman and Ruby, both 76, have embraced Shippen’s legacy in different ways. Ruby was a student in 1993 at Union County College (in Cranford, New Jersey). A professor saw a Black History Month piece written by the Newark Star-Ledger’s Jerry Izenberg about Shippen and asked Ruby if she would return a paper on Shippen to satisfy requirements of an African American Studies course.

Thurman found Shippen’s story so compelling that when prompted by the mayor of Scotch Plains to advance the legacy, he and his wife founded the John Shippen Memorial Foundation in 1998.

“We wanted to keep the focus,” said Ruby. “It’s not just important for John Shippen, but to keep history preserved and our contribution to this country and the world of sports.”

Thurman and Ruby set up a Shippen museum at the municipally-owned Scotch Hills Country Club, and have both played there in recent years. For 12 years, they also operated the John Shippen Youth Golf Academy and junior tournament. The academy was led by volunteer coach John Perry, a photojournalist for African American Golfer’s Digest, whose move to Florida closed the academy.

Though the academy has closed, the couple still plans to award $1,000 scholarships to students in surrounding communities.

Back when the academy was still open, participants had to take a quiz on Shippen.

“We gave a test about golf etiquette, who John Shippen was and his contribution to the game of golf,” said Perry. “The Simmons raised money for the foundation that included a headstone for Shippen’s grave in New Jersey.”

The search for scholarship recipients continues, said Ruby, who is a consultant for a local charter school. “We tried for three years to get a commemorative stamp honoring John,” she said. “But that petition was turned down by the U.S. Postal Service. It is so hard to have the support for that and keep it going.”

Trying to achieve proper recognition for Shippen, Thurman Simmons points to one ill-fated golf moment that flipped historic momentum.

It came in 1896, at the second U.S. Open at Shinnecock where Shippen made his major championship debut. Entering the Open with his friend Oscar Bunn, a Native American, the pair were met with a written protest led by a group of fellow competitors dominated by Scottish and English professionals. The group said that they would not play if Shippen and Bunn were allowed in the field.

USGA President Theodore Havermeyer responded, “Gentlemen, you can leave or stay as you please. We are going to play this tournament tomorrow - with or without you.” They stayed and played. Shippen posted rounds of 78 and 81 - the latter the result of a disastrous 11 on the 13th hole at Shinnecock Hills - and tied for sixth place.

“If not for that one hole,” said Thurman Simmons, “we wouldn’t be having this conversation about a Black professional who was forgotten.”

The Simmons’ quest to educate the next generation continues.

“I’m hoping that the Scotch Plains Recreation Department will continue to support the museum,” said Thurman. “We look to keep scholarships going. It’s hard to find a coach as dedicated as the one (Perry) we’ve had. We have done almost as much as we can. It doesn’t seem that nobody wants to take on that task.

“Shippen, who is the first American-born golf professional, will always have his place in history. I don’t have a platform to get up in front of a big golf group. When the Open is at Shinnecock, John Shippen’s name comes up. Then, it is dropped from that point on. We look for others to pick up the story and don’t let it drop.”